por Gastón Laborido (gaston_laborido1@hotmail.com)

El Uruguay independiente

Entre 1825 y 1830 se generaron acontecimientos que dieron como resultado la formación del Estado Oriental independiente. Los sucesos transcurren desde la formación de un Gobierno Provisorio en Florida y que tendrá como episodio relevante la Convención Preliminar de Paz, celebrada en 1828 entre delegados del Imperio del Brasil, de las Provincias Unidas y de Inglaterra, bajo la mediación del Lord John Ponsonby. Los resultados de esta Convención fueron ratificados el 4 de octubre de 1828.

Uno de los puntos de la Convención Preliminar de Paz, estableció que se debía instalar un Gobierno Provisorio y una Asamblea Legislativa Constituyente que tendría como tarea elaborar la primera Constitución del Uruguay, jurada el 18 de julio de 1830. Así, se inició el Estado Oriental del Uruguay como libre e independiente. En los primeros años de vida independiente, la población del país era escasa, los historiadores estiman que en 1830 había 74.000 habitantes, de los cuales 14.000 estaban en Montevideo. A partir de 1830, se intensifica la afluencia creciente de emigrantes europeos como vascofranceses o españoles, los italianos (genoveses), canarios, gallegos, ingleses, suizos, que llegaron a 42.000 entre 1836 y 1842.

La llegada de inmigrantes europeos entre 1830 y 1840, implicó crecimiento del tráfico marítimo en el Puerto de Montevideo; por otra parte, el comercio exterior se acentúa. El aporte de los inmigrantes europeos fue fundamental para el desarrollo económico del país y para el desarrollo del deporte en el Uruguay, aunque aquellas primeras manifestaciones se caracterizaban por su vaguedad e imprecisión.

La situación del naciente Estado Oriental era crítica, luego de varios años de revolución y lucha por la independencia (1810-1830). La elección del General Fructuoso Rivera como primer Presidente de la República, el 24 de octubre de 1830, no auguraba una pronta resolución de esos problemas.

El Estado Oriental del Uruguay presentaba un atraso económico caracterizado por la monoproducción ganadera con un sistema de explotación arcaica. A esto, le sucedió la Guerra Grande (1839-1851), que involucró las tendencias políticas del Uruguay y la Confederación Argentina (blancos y colorados: federales y unitarios), el Imperio del Brasil y las potencias industriales en expansión como Inglaterra y Francia. Luego de la Guerra Grande, es que se roturaron tierras. En cuanto al sistema de propiedad, en el medio rural predominó, hasta el día de hoy, el latifundio. En consecuencia, surge un antagonismo entre el campo y la ciudad como núcleos opuestos.

Montevideo: la “Ciudad Vieja” y la “Ciudad Nueva”

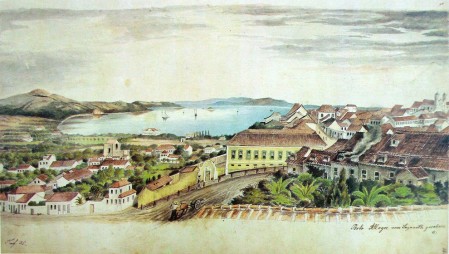

De acuerdo a Gerardo Pérez (2020), “Montevideo nace como una ciudad para proteger la zona y, por tanto, va a ser parte de un circuito defensivo de las posesiones españolas” (p. 43). Por este motivo muchas de sus construcciones principales fueron pensadas y ejecutadas con el ese objetivo: defender. Esto explica también porque Montevideo fue una ciudad fortificada. Con el comienzo de la vida constitucional del Estado Oriental del Uruguay, se decide tirar las murallas de la Ciudad de Montevideo, “(…) como un gesto que buscaba dejar atrás un período de dominación extranjera y marcar un nuevo comienzo. Con esto, la ciudad cambiará lento pero constante. Será el momento de pensar en la Ciudad Nueva” (Pérez, G., 2020, p. 52).

El nombre de Ciudad Vieja aparece como contraposición al proyecto de “Ciudad Nueva”, que se crea en 1829 a instancias del Coronel José María Reyes (1803-1864); militar argentino radicado en territorio Oriental desde 1828 hasta su muerte. Dentro de ese predio, que iba dese la puerta de la Ciudadela hasta la actual calle Yaguarón, se comenzó a extender la ciudad. Una de las consecuencias que trajo la concreción de este proyecto, fue el nacimiento de nuevos barrios que marcaron la expansión de la ciudad.

Dentro de aquel perímetro delineó Reyes la “nueva ciudad”, compuesta de 136 manzanas de cien varas de lado, y dos plazas que corresponden aproximadamente a la mitad este de la actual plaza Independencia y a la actual plaza Cagancha; ese trazado, con pocas modificaciones, subsiste aún para la parte de Montevideo comprendida entre las calles Florida, Galicia, Médanos e Isla de Flores, que es la “Ciudad nueva” propiamente dicha. (Castellanos, A., 1971, p. 3).

Después de la independencia, la población de Montevideo había aumentado sensiblemente. Un censo de 1835 daba a Montevideo una población de 23.404 habitantes, de los cuales 14.390 correspondían a la planta urbana y 9.014 a lo que sería la nueva ciudad. El aumento población en relación a 1829 fue del 67,1 %.

El mismo censo señalaba 1.012 propietarios y 2.024 inquilinos en la planta urbana, 536 propietarios y 2.024 inquilinos en la planta urbana, 536 propietarios y 578 inquilinos en extramuros; 590 casas de comercio; 290 artesanos y jornaleros: 38 tambos; 19 atahonas; 36 hornos de ladrillo; 16 locales para culto religioso. (Castellanos, A., 1971, p. 4).

.

.

La plaza de toros del Cordón y sus representaciones literarias (1835-1842)

Durante el siglo XIX, Montevideo tuvo diversas actividades recreativas y algunas de ellas incluían el empleo de animales. Las prácticas de entretenimiento de una sociedad permiten la comprensión de la dinámica social de una población y puede ser muy útil para la comprensión histórica de la estructura socio-cultural de una época.

En el caso montevideano, eran espectáculos muy recurrentes que aglomeraban a muchas personas. Varios de ellos se caracterizaban por el castigo físico tanto con hombres como con animales. De alguna manera era el reflejo de una sociedad marcada por el espectáculo de la sangre y la muerte, que estaban en todos lados. El historiador José Pedro Barrán (2021) describió la sensibilidad del 1800 a 1860 como la “cultura bárbara” y enfatizó en la cuestión del castigo del cuerpo. En este sentido, afirma que “el castigo también incluyó el cuerpo de los animales, sirviendo con frecuencia el hecho mismo de espectáculo y diversión pública” (Barrán, J. P.; 2021, p. 79).

En ésta época tuvo importante difusión las corridas de toros, que comenzaron antes de la Independencia, con varias “plazas” en la Ciudad Vieja. Después de las corridas de toros de la Plaza Matriz (1823), no se dieron más corridas de toros hasta 1835, cuando pasaron al Cordón, barrio que formó parte de la expansión de la ciudad de Montevideo en la primera mitad del siglo XIX y actualmente es parte del centro de la ciudad.

La plaza de toros del Cordón quedaba contigua a la quinta de Ramón Masini (que fuera miembro de la primera Asamblea General Constituyente). Fue construida por la empresa Sierra y Anaya. El establecimiento funcionó hasta el año 1842, cuando fue derribada por motivos de defensa de la ciudad sitiada por las tropas “blancas” del general Oribe.

Isidoro de María (1815-1906), quien en sus crónicas recogidas en Montevideo Antiguo nos pinta parte de esa realidad y notables descripciones de las corridas de toros señala que a esta plaza “se iba de jarana por 6 vintenes en carretilla (…)” (De María, I., 1957, p. 44).

Por otro lado, en los inicios del Uruguay independiente se da un proceso en el cual, parte del grupo de políticos-intelectuales descubren las posibilidades de la poesía como herramienta política y se ambientó la querella entre neoclásicos y románticos (Peruchena, 2016). En este proceso, los neoclásicos traducen obras como Horacio, mientras que los románticos traducen a Byron o a Chateaubriand, sustituyendo lecturas hispánicas como a Quintana por José Zorrilla o a Espronceda, así como tienden a lo sentimental y lacrimoso. La relación entre política y poesía fue muy fuerte en este período:

(…) queda demostrada con las convocatorias oficiales a certámenes poéticos públicos. A modo de ejemplo recordemos el Certamen Poético que convocara el jefe político de Montevideo en 1841 en celebración del 25 de mayo de 1810. Se presentaron once originales y obtuvo el primer premio Juan M. Gutiérrez, tal vez el menos romántico de la generación, dictamen que podría explicarse señalando que el jurado estuvo integrado por personalidades de tendencias literarias neoclásicas como Francisco Araúcho, Manuel Herrera y Obes, Juan A. Gelly, Cándido Joanicó y el emigrado argentino Florencio Varela. (Peruchena, L., 2016, p. 240).

Uno de los representantes neoclásicos, fue Francisco Acuña de Figueroa (1791-1862), quien nació en Montevideo y murió en la misma ciudad. Suele ser considerado el primer poeta nacional, con profunda influencia del clasicismo y un atinado ingenio para la poesía satírica. Además entre la vasta producción del mencionado poeta cabe destacar la letra de los himnos nacionales de Uruguay y Paraguay.

Acuña de Figueroa pertenecía a una familia de altos funcionarios españoles en la época colonial, recibió una formación clásica de la que no se apartó, a pesar de los sucesivos y profundos cambios ideológicos y políticos que le tocó transitar, y de los que dio testimonio en su cuantiosa obra. Fue, en su época, “el poeta de Montevideo”. Además, políticamente fue oficialista toda su vida, celebrando en sus obras al gobierno de turno.

También se lo considera como un buen latinista y conocedor de lenguas modernas, ya que tradujo obras clásicas y contemporáneas, incorporó formas y ritmos populares, compuso poemas visuales, epigramas, anagramas, acrósticos en los que celebra, entre loas y burlas, una gran variedad de estampas.

A su vez, le dedicó en sus obras crónicas en versos a las corridas de toros. Por lo tanto, la tradición taurina montevideana en lo literario fue iniciada por el poeta Francisco Acuña de Figueroa, a través de sus celebradas “Toraidas”, tal como las llamó, dignas de perpetuarse en el tiempo, por su donosura y gracejo. Estas crónicas eran versos que referían a la fiesta brava y en las cuales el poeta dio cause a su pasión por las corridas de toros:

«Un género del que puede considerarse inventor a Figueroa es el de las Toraidas… Las incidencias de estos espectáculos… relatadas por un versificador de la fluidez y el gracejo de D. Francisco, que, por raro caso, era a la par un perito en todos los aspectos del arte de Pepe-HiIllo y Costillares, atraen al lector, que reconstruye con su imaginación, el aspecto de las multitudes abigarradas y rumorosas asistentes a los cosos en que se efectuaba la fiesta brava». (Bracco, D., 2006, p. 209).

No todas las toraidas de Acuña de Figueroa fueron publicadas. Algunas de ellas fueron las tituladas: bombástica, con morrión romántica, técnico – jocosa, toruna, anticlásica, de Aleluya, rabona, enana, joco – política, y encomiástica.

Francisco Bauzá (1849-1899) fue un historiador, profesor universitario, periodista, ensayista, legislador uruguayo, su obra constituye uno de los grandes monumentos de la historiografía uruguaya y americana tratando de responder interrogantes que se planteaban sobre la identidad nacional. Entre tantas cosas que escribió Bauzá, una de ellas fue sobre Francisco Acuña de Figueroa en 1885 en su obra Estudios literarios, en la cual analizó la producción de Acuña de Figueroa sobre las Toraidas. Primeramente Bauzá, fiel a su estilo decimonónico, caracterizó a los espectáculos taurinos de la siguiente manera:

(…) Para pintar en toda su deformidad esta clase de espectáculos, conviene decir previamente alguna cosa sobre ellos. Forma la parroquia habitual de las corridas, el más inapropiado público que pueda darse. Vecinos honestos que se desvanecerían ante las perspectivas de matar un animal cualquiera en su casa; profesores de derecho natural que sostienen la inviolabilidad de la vida en todo organismo dotado de actividad voluntaria; médicos que se compungen de las enfermedades de los animales y enseñan a los veterinarios a curarlas; economistas que toman a punto de honra defender la industria pecuaria, católicos sinceros que leen con atención reverente aquel precepto del Deuteronomio que dice: “no verás el buey de tu hermano o su cordero, perdidos, y te esconderás de ellos: volviendo, los volverás a tu hermano”; en fin, personas nerviosas y caritativas, de todo linaje y condiciones, se sientan en las gradas de piedra del hemiciclo, y esperan alegres el sangriento espectáculo, después de haberse recíprocamente informado con el más correcto ceremonial inquisitivo sobre la salud de todos los suyos. Y estos filántropos, cuya condición humanitaria trasciende a sus doctrinas, resultan como tocados de epilepsia al sonido de la corneta que anuncia la aparición de unos cuantos chulos ridículamente pergeñados, electrizándose hasta delirar, cuando estos con esguízaro lengüeteo ofrecen por complemento de sus maniobras unas cuantas bestias muertas a puntazos y cuchilladas. (Bauzá, F., 1953, p. 19-20)

Bauzá (1953) plantea que “la prosa es impotente para describir toda la grandeza de un espectáculo semejante. A no tener la poesía el atractivo secreto de la rima, la estructura férrea de la estrofa, el fugitivo destello de la inspiración, no fuera tampoco digna de cometido tan excelso” (p. 23).

En Toraida Romántica (1838-39) Acuña de Figueroa se enojaba con Mendo, quien criticaba la tauromaquia:

Grita Mendo

que es horrendo,

que es infando,

ver lidiando

racionales

y animales;

que es un juego

musulmán:

Y el vestiglo

diz que el siglo

de las luces,

dio de bruces

sin decoro

porque hay toro:

¡Qué pasiego!

¡Qué patán!

Numerosos indicios del modo en que se desarrollaba la fiesta taurina pueden encontrarse en cada una de las composiciones de Acuña de Figueroa. Por ejemplo, la jornada popular que obligó a la autoridad a prohibir por muchos meses las lidias de toros, con profundo sentimiento de una gran parte de la población. Así se refirió el poeta:

En plena posesión como unos reyes

estábamos del circo, en paz profunda,

cuando violando las taurinas leyes

se amotinó una plebe furibunda;

y sobre si eran toros, o eran bueyes,

hubo escándalo, asalto y barahunda,

hasta que allí volar vieron mis ojos

tablas, sillas y bancos por despojos.

Yo vi ultrajada en el saqueo infando

la pica de Palanca… ¡oh, lance fiero!

pica que honrara el noble Villandrando,

¡y en qué manos!.., en manos de un lechero!!!

Vi una ninfa en gran riesgo reclamando

contra el vulgo frenético y grosero,

yo la vi, en un tablón que se derrumba,

como el ángel de luz sobre la tumba.

A Repollo y Violín llamaba airado

el vulgo en el furor que le enajena;

mas el violín estaba destemplado

y el repollo cual blanda berenjena.

Asustados los dos, bajo el tablado

¿quién sabe lo que hacían en tal pena?

¡Ay, no salgas, escóndete Repollo,

que eso sería echarle trigo al pollo!

Allí vendióse en bárbara subasta

y a vil precio la espada de García.

Dulces vi por el suelo en caldo y pasta,

y una lluvia de almendras y arropía.

Un confuso tropel, de varia casta

¡A la mosca! y ¡al mono! repetía

y al boletero asaltan con encono;

mas ya estaban en salvo mosca y mono.

Francisco Bauzá analizó estas cuatro estrofas y plantea:

No puede describirse con más propiedad en cuatro estrofas, un lance tan sonado y tan terrible. Todas las peripecias de la lucha, están marcadas con precisión maravillosa. La tranquila actitud de los espectadores antes de la gresca; lo inesperado de la rebelión popular; la transformación en pájaros de las sillas, tablas y bancos para volar sobre la cabeza de los toreros, la deshonra del picador Palanca, Bayardo de la tauromaquia, a quien un lechero había quitado sus armas; los apuros de García condenado a presenciar la bárbara subasta de su espada vendida a vil precio; la resignación de Repollo y Violín, acurrucados bajo el tablado, haciendo quién sabe qué; y por último, las profundas vistas del boletero, poniéndose en salvo a tiempo con la mosca, como si presintiera que por allí debía concluir obligatoriamente la función y toda función comenzada de esa manera; dan una idea bien cumplida de lo que es un lance de tal laya. ¡Y pensar que hay quien quiera prohibir al pueblo goces tan inocentes! (Bauzá, F., 1953, p. 19-20)

Queda en evidencia que el episodio que describe Acuña de Figueroa da cuenta de la “sensibilidad bárbara” característica del Uruguay del 1800 a 1860 aproximadamente. El historiador José Pedro Barrán (2021), definió a la “barbarie” como “la sensibilidad de los “excesos” en el juego y el ocio (su consecuencia improductiva), en la sexualidad, en la violencia, en la exhibición “irrespetuosa” de la muerte (…)” (p. 12).

Referencias:

-

- BARRÁN, José Pedro (2021). Historia de la sensibilidad en el Uruguay. Montevideo: Banda Oriental.

- BARRIOS PINTOS, Aníbal (1971). Los barrios (I). Montevideo: Nuestra Tierra.

- BAUZÁ, Francisco (1953). Estudios literarios. Montevideo: Biblioteca Artigas.

- BRACCO, Diego (2006). Apuntes para la historia de la tauromaquia en Uruguay. En: Revista de Estudios taurinos; v. 1 (n° 22), Murcia (pp. 203-247).

- BUZZETTI, José y GUTIÉRREZ CORTINAS, Eduardo (1965). Historia del deporte en el Uruguay (1830-1900). Montevideo: Ed. De los autores.

- CASTELLANOS, Alfredo (1971). Montevideo en el siglo XIX. Montevideo: Nuestra Tierra.

- DE MARÍA, Isidoro (1957). Montevideo Antiguo. Tomo I. Montevideo: Biblioteca Artigas.

- GOMENSORO, Arnaldo (2015). Historia del Deporte, la Recreación y la Educación Física en Uruguay. Crónicas y relatos. Montevideo: IUACJ.

- PÉREZ, Gerardo (2020). Un barrio, mil historias. Montevideo en el pasado, presente y futuro. Montevideo: Aguilar.

- PERUCHENA, Lourdes (2016). La cultura y sus tendencias. En: G. Caetano (Dir.) y A. Frega (Coord.), Revolución, Independencia y construcción del Estado (pp. 223-269). Montevideo: Planeta.

Escrito por Victor Melo

Escrito por Victor Melo

Você precisa fazer login para comentar.